HISTORY OF THE SCHOLARSHIP

ORIGINS

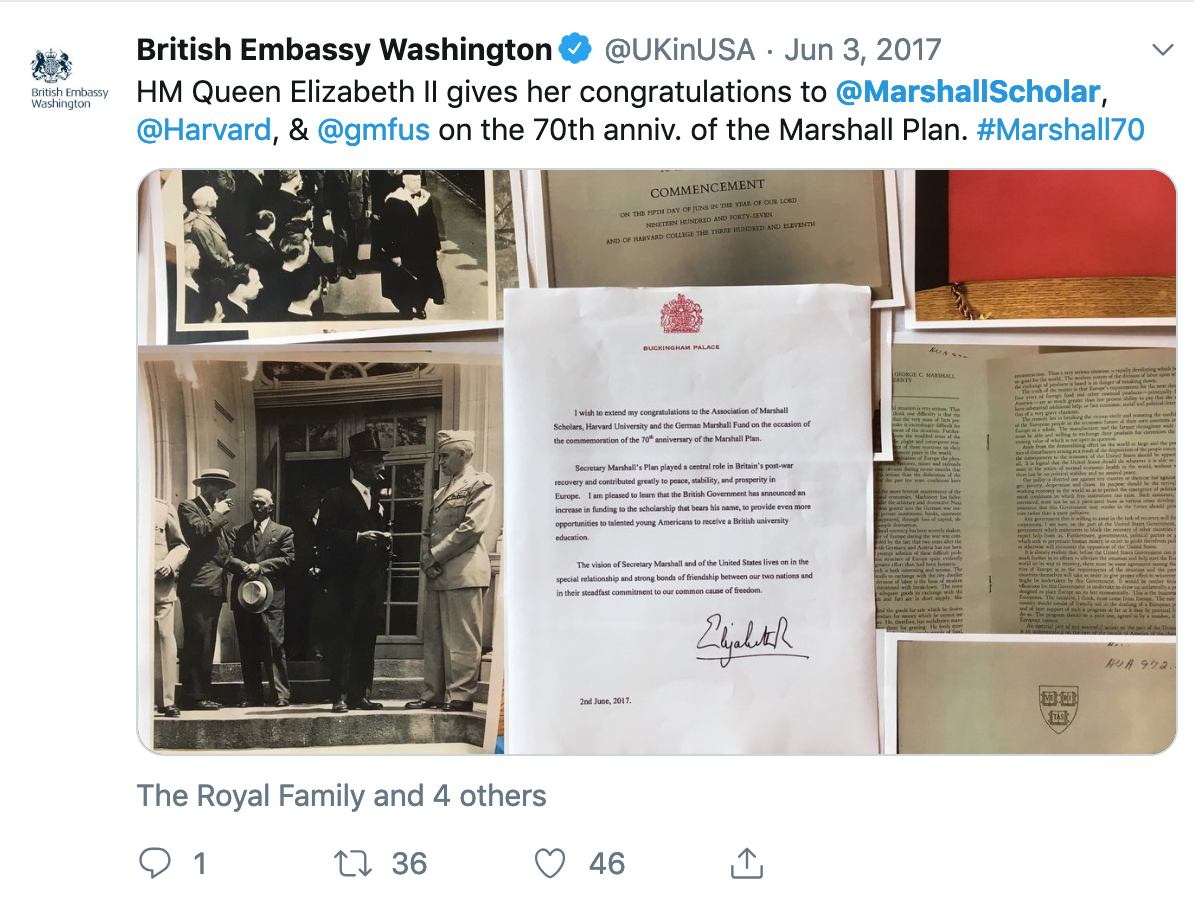

The origins of the Marshall Scholarship lie in an expression of Britain’s gratitude to the United States for post-WWII aid in the form of the Marshall Plan. The concept of a scholarship as both fundamentally a tool of diplomacy and also as an enduring expression of gratitude was, from its conception to the white paper that led to its enactment, largely an effort of the Foreign Office.

In 1949, there was a suggestion by Sir Roger Mellor Makins, the then British Deputy Undersecretary of State, to establish an academic scholarship scheme in the UK for American college graduates. Makins recommended it be called “The Marshall Scholarship,” pending approval from the then US Secretary of State Dean Acheson and the Scholarship’s proposed namesake, former Secretary of State General George C. Marshall.

Makins then sought the counsel of several individuals before introducing the Scholarship timeline and proposal to the Prime Minister. He consulted the Treasury and Education Departments, the Rhodes and Fulbright Scholarship administrations, the UK’s Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals (CVCP), as well as, individually, the British Ambassador to the USA and the heads of the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, London, and Glasgow. Not only did these consultations provide Makins and other Foreign Office officials with a wide range of constructive criticism and advice but they also allowed them political leverage to claim viability and approval from key leaders in higher education.

PROPOSALS

“We think it would be wrong to tie the scholarships to any particular universities...”

Makins’ original proposal accounted for six scholars at the University of Cambridge. The number six appears to have been arbitrary, and Cambridge was picked because of its historic rivalry with Oxford, which already hosted the Rhodes Scholarship. The prospect of limiting to a single institution, however, drew criticism from other circles in government. “We think it would be wrong to tie the scholarships to any particular universities,” advised Sir Edward Hale, Secretary to the University Grants Committee, an advisory committee to the British government on grant distribution, to a Treasury official involved in the matter. “A private benefactor can do that sort of thing, not the Government... [To] make a short list of this kind is an invidious business which I am sure my Committee would decline to undertake.”

One month later, Makins called a joint meeting between Treasury, Foreign Office, and Education officials. The group decided that it would be unwise to discriminate in favor of any one institution, so Cambridge was replaced by a free choice of university within the UK.

This choice is an enduring characteristic of the Scholarship to this day, and remains one of its most important core tenets.

Though the primary impetus behind the Marshall Scholarship was gratitude for Marshall Aid, British officials (Makins included) also hoped it would produce a positive effect on Anglo-American relations in perpetuity. Early in the process, a Treasury official noted: “In the long run I think everybody would agree that the idea has great attractions. Certainly all those who have had to deal officially with Americans will pay tribute to the value of the leaven of Americans who have been educated in British universities.” Most officials, though, merely believed the scheme would “have a favourable effect on American opinion” and “pay [the UK] the best dividend in the form of increased understanding and goodwill.”

THE FIRST MARSHALL SCHOLARS

“In appointing Marshall scholars the selectors will look for distinction of intellect and character...”

Cabinet discussions surrounding the Marshall Scholarship were short but heated. Controversial topics, as within Foreign Office debates, included the familiar issues of age limit, stipend amount, and the marital status of candidates. After three separate Cabinet meetings, although all of the issues had not been completely resolved, the Cabinet approved of the scheme in principle:

Her Majesty’s Government have decided to give effect to the proposal of the late Government to express the United Kingdom’s gratitude for this generous and far-sighted programme for European recovery by founding at British universities 12 scholarships to be competed for annually by United States students. These scholarships will be open to men and women and will be tenable at any British university. General Marshall has agreed that these scholarships shall be known as “Marshall Scholarships.” The Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals of the Universities of the United Kingdom has promised its full co-operation in giving effect to this scheme. Further particulars will be announced in due course and Parliament will be asked to make the necessary financial provision.

As expected, the announcement garnered widespread media attention across the UK and USA. In response, the US State Department issued the following statement:

The generous offer made by the British Government is received with sincere appreciation and gratitude by the Government of the United States. It is not only a splendid expression of British friendship for the United States, but is also one more important step in furtherance of mutual understanding between our two countries.

As for the selection of candidates, the white paper outlined general guidelines for the selection committees, invoking General Marshall himself:

In appointing Marshall scholars the selectors will look for distinction of intellect and character as evidenced both by their scholastic attainment and by their other activities and achievements. Preference will be given to candidates who combine high academic ability with the capacity to play an active part in the life of the United Kingdom university to which they go. A Marshall scholar, as the possessor of a keen intellect and a broad outlook, would be thought of as a person who would contribute to the aims which General Marshall had in mind when, speaking at Cambridge, Massachusetts, on the 5th of June, 1947, of economic assistance for Europe, he said, “An essential part of any successful action on the part of the United States is an understanding on the part of the people of America of the character of the problem and the remedies to be applied. Political passion and prejudice should have no part. With foresight, and a willingness on the part of our people to face up to the vast responsibilities which history has clearly placed upon our country, the difficulties... can, and will, be overcome.”

The bill was approved by Parliament and became a formal Act of Parliament, “The Marshall Aid Commemoration Act of 1953,” on 31 July 1953, and the first class of Scholars journeyed across the Atlantic to the United Kingdom in the fall of 1954.